WHAT A BOOK CAN BE?...

I GUESS THIS DEBATE IS A LONG AS BOOKS ARE AROUND. AS NOTION FOR WRITTEN WORD THAT WE KNOW - for centuries. As an object in its own right? - not very long. The debate is open and lively.

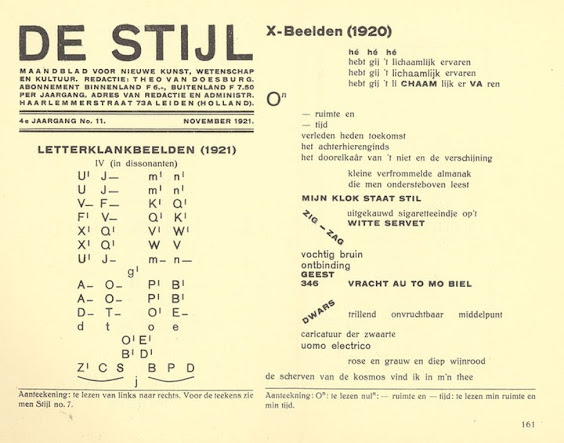

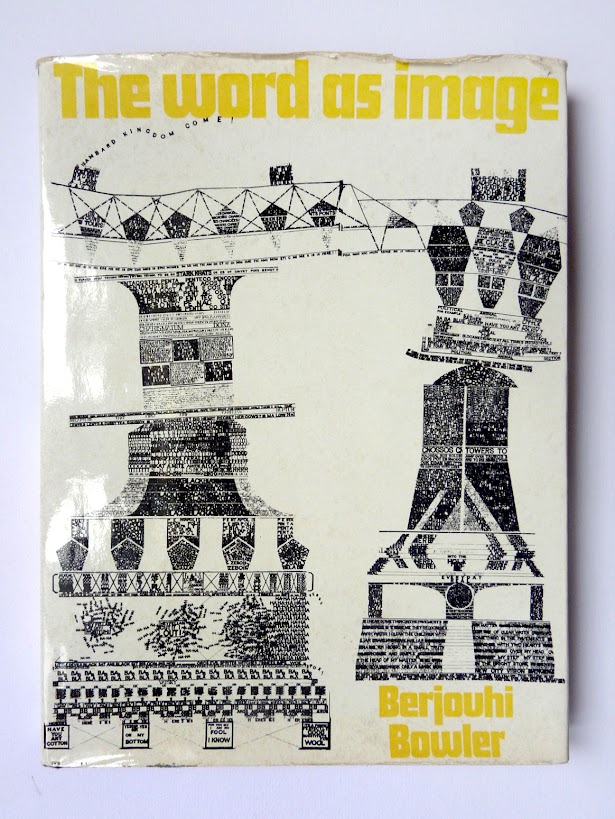

AT THE BEGINNING OF 20TH CENTURY ARTIST BEGAN TO RETHINK THE IDEA OF A BOOK AND LANGUAGE IN GENERAL:

Things started to become more abstract, fitted with new and modern concepts of deconstruction and availability.

"CAN BOOKS WITHOUT MUCH EXPLANATION, WITHOUT BEING READ EVEN, SAY SOMETHING?" - Ms Virginia Bartow on 'Ninety from the Nineties: A Decade of Printing' at the New York Public Library

[Accessed 6.12.20]

''Ninety From the Nineties: A Decade of Printing'' is an exhibition built around a conundrum that lies at the center of most surveys of the book as object. The tension centers on purpose: books, which we are accustomed to thinking of as containers -- and conveyers -- of information, are placed in a context in which form is valued over content.

Language is less important than the type that impresses it on the page. The paper counts for more than the story told on it. The illustrations and the binding might be the story. Words? Who needs 'em?

O.K., that may be extreme, though this cavalier -- or perhaps more accurately, cheeky -- attitude does seem present in some of the more inventive letterpress books on display at the New York Public Library, where Virginia Bartow has put together an exhibition that has a long tradition there. (Previous surveys considered the 1960's, 70's and 80's.)

Ms. Bartow herself seemed aware of the puzzle at hand. Asked what drove her as she winnowed down to 90 the more than 4,000 letterpress books the library acquired in the decade in which they were made, she replied with a question that the show obviously hopes to answer in the affirmative: ''Can books, without much explanation, without being read even, say something?''

Before this is sorted out, it's probably worth understanding the terms of the show. The library has a policy of buying books made by American and European presses that follow in the tradition of the private-press movement, set in motion by William Morris and the Kelmscott Press in London at the end of the 19th centur.

In an increasingly industrialized world, Morris's goal was to reintroduce dedicated craftsmanship into the printing and binding of books. Using fine paper, typefaces based on calligraphic letter forms, decorative illustrations and aesthetic bindings, Morris sought to ''recapture the beauty and harmony of an earlier age,'' as Ms. Bartow puts it in her pamphlet accompanying the show.

A hundred years later his followers draw on the same vocabulary, though naturally many of them seek to deploy it to different ends. Morris's models were medieval manuscripts and early printed books; his descendants are not always so backward-gazing. Frequently the only thing they have in common with their progenitor is the most basic rule Ms. Bartow applied to the books she collected for the library: that they be the result of a relief-printing process, in which a surface has been inked and pressed to paper. This alone links them to Gutenberg; everything else is up for grabs.

The surprising thing about ''Ninety From the Nineties'' is the imaginative energy that is freed by this simple constraint. While Ms. Bartow insisted that artists' books were outside her purview, the best of the books here reflect considerable artistry. A number seem perfunctorily chosen, perhaps because their task is to fill out the exhibition's five sections: ''Binding,'' ''Type,'' ''Paper,'' ''Illustration'' and ''Inspiration.'' But as can happen with these shows, it's not the specific categories so much as the interconnections within them, the unspoken themes that occur as if by accident, that create the most interest.

Experimentation is certainly one of them. The urge among these printers to play with their materials and methods, the structure and illustration of their books, is palpable. At times it forces the basic question: What is a book, anyway? Is it Susan Lowdermilk's accordion-folded woodcut portrait gallery of her family (''All My Relations,'' Lone Goose Press.

All My Relations Artist Book | Susan Lowdermilk [Accessed 6.10.21]

What about Sara Karig's ''Vorkuta Poems'' (Dobbin Books), in which a molded-paper three-dimensional head created by Louise McCagg eats a miniature volume of Ms. Karig's verse? You have to take it on faith, since the mouth tightly clamps the language, that the poems can even be read.

Not all experiments are extreme. A workshop sponsored by the Book Arts Guild of Seattle shaped a folded sheet of paper to resemble a paper airplane and used bubble wrap to print background texture; if folding is sufficient to turn paper into a book, then a paper airplane seems an almost inevitable end form.

Markus Müller has rendered designs by Adrian Frutiger as bold watermarks (Basle Paper Mill), a reminder that there is often hidden beauty built into the very flesh of a book, while Russell Maret has adapted engravings of period commedia dell'arte figures into photo-etched metal cuts (Kuboaa Press). He has printed them with watercolor paint, which makes the classic images seem unpredictably handsome, blurred and modern.

Is it old-fashioned to single out for praise books that marry shape or form to content in a way that creates a reverberation between the two? Isn't this a reasonable ideal? For Mark Twain's ''Innocents Abroad'' Trisha Hammer has created a binding and box that together resemble a traveling case, and Heather McAdams has provided 20 pages of illustrations, made while she retraced Twain's itinerary (Sherwin Beach Press). The results are witty and wry.

Catherine Ferguson's triptych-shaped prints and Donna Pierce's text come together in ''New World Saints,'' whose portfolios are also shaped like a triptych (Press of the Palace of the Governors); there is a hint here of the backward glance -- toward the medieval -- that might please Morris. And Linda Smith's ''Dam Domino Book'' (Picnic Press) is a visually and formally inspired pop-up book that demonstrates the environmental effects of the damming of rivers. When the book is opened, a dam rises. When tabs are pulled, riverine wildlife and plants spring up; when the tabs are let go, the wildlife and plants fall like dominoes on the page.

One thing iconoclastic books can do terrifically is provide commentary, whether textual or visual, on the primary content of a book. A subtle example is Greta D. Sibley's ''Tea: Time in Korea'' (Small Offerings Press), whose paper boards feature images of a tea blossom, cup and saucer, and the Korean character for tea.

More elaborate is Lois Morrison's self-published ''Baucis and Philemon,'' from Ovid's ''Metamorphoses,'' in which paper-cut illustrations depict Baucis and Philemon as human beings and as the trees (linden and olive) into which they were transformed after Jupiter and Mercury repaid the couple's hospitality by granting them their wish that, after death, they could go on living together forever.

Lynne Tillman's ''Bad News: A Short Story'' (INK-A! Press) juxtaposes an imagined story with the actual running commentary from WINS in New York, the all-news radio station that inspired it. (Different typefaces and colored inks distinguish the texts.)

Janus Press has come up with an exceedingly clever solution to Denise Levertov's ''Batterers,'' a poem whose author remained unresolved about the order of her stanzas and had previously published them in two forms: the book can be manipulated so the stanzas can be read 1-2-3 or 1-3-2, reflecting Ms. Levertov's indecision. Now this is form serving content in the best sense.

Collaboration seems, well, bound into the craft of bookmaking. Papermakers, typesetters, typemakers, printers, illustrators, binding designers and binding fabricators can all be separate people; how suitable then to find so many books here that embrace partnership in various ways. Jim Gelfand, an artist and a grandson of the printer Morris A. Gelfand, worked with his grandfather on ''Where I Live: Environments'' (Stone House Press), which includes photographic prints of the rather eccentric installations that the younger Mr. Gelfand places throughout his New York apartment.

Nadja Press published ''David Jackson, Scenes From His Life,'' a pairing of illustrations by Mr. Jackson and text by James Merrill that chronicles Mr. Jackson's (thus, also, Mr. Merrill's) life and travels in Greece and elsewhere, suitably bound in Aegean blue.

David Jackson: Scenes from his Life. Texts by the artist and James Merrill - James Merrill - First edition, one of 100 copies hors commerce (jamescumminsbookseller.com) [accessed 6.01.21]

The most memorable of these 90 books are often the ones that push maybe just a bit too hard the definition of what a book is, or might be. Julie Chen's ''Bon Bon Mots'' (Flying Fish Press) consists of five miniature books that fit into, and resemble, a box of chocolates. The mots legible are not particularly bon (''I forgot to notice myself''), but the idea of stretching a book in this way manages to captivate, nonetheless.

In ''Howards & Hoovers'' (Bitchy Buddha Press) Indigo Som uses screwposts to bind lists of Chinese-American masculine names; the results resemble a paint chip selector, a pre-existing booklike form you might not have thought of as such.

Then there's ''Agrippa (a Book of the Dead),'' a collaboration between William Gibson, the science-fiction writer, and Dennis Ashbaugh, an artist. (Kevin Begos Jr. was the publisher.) The poem has been -- try to follow this -- encoded in the letters C, A, T and G; they represent the first letters of the quartet of nucleic acids in DNA: cytosine, adenine, thymine and guanine.

Editorial - Victoria and Albert Museum (vam.ac.uk) [Accessed 6.01.21]

2006AN6710.jpg (512×768) (vam.ac.uk) [Accessed 6.01.21]

Among Mr Ashbaugh's prints are two photosensitive images that either appear or disappear when exposed to the light. The poem itself, on a floppy disk, becomes encrypted as soon as it has been downloaded and can never be accessed again. Although Ms Bartow admitted to a surreptitious glimpse, the book has never been fully opened. But there it sits among its admittedly tamer cousins in one of the Edna Barnes Salomon Room's august tilted, glass-fronted cases, enigmatically doing its part to answer the exhibition's prevailing question.

So once again: can books, without even being read, say something? The answer would be a provisional yes; some can. And if it's not always clear what these books are saying, exactly, at least in saying it, or trying to, their fabricators seem to have had a good time.

Of course, they can and they should! Even more so in today's world, where books are undergoing complete digitalization (e-books, e-literature, online platforms, etc.)

Still, however, the tactile quality and physicality of a book are important and the publishing industry is booming.

PROPOSITION

Comments

Post a Comment